“This is no way to live”, Public security and right to life in Venezuela

The diagnoses presented below are derived from Amnesty International's research on armed violence and the public security situation in Venezuela from a human rights perspective. This includes a historical overview of the measures implemented by the state to address crime, as well as the identification of patterns of institutional violence and human rights abuses in the framework of public security operations.

Amnesty International was able to determine that the Venezuelan state is responsible for violations of the right to life and physical integrity of hundreds of victims on two levels. Firstly, the state has failed to guarantee the right to life in a context of violence between private individuals. And secondly, the state has implemented repressive measures, adopting military methods, in responding to crime, that have led to serious human rights violations, in particular extrajudicial executions.

In addition, Amnesty International was able to identify how the repressive policies adopted by the Venezuelan authorities have resulted in the social criminalization of poverty. Instead of implementing preventive measures to control crime, the state has resorted to the intentional use of lethal force against the most vulnerable and socially excluded sectors of the population.

Living in a working class neighbourhood and being a young man are the top criteria for you to be killed. That means you can't be young anymore, because who are they targeting? The young. Jennifer Rotundo, mother of Luis Ángelo Martínez, who died at the hands of alleged police officers1

The research was carried out in a context of lack of access to economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to health and food, to the failure to respect and guarantee civil and political rights, such as freedom of expression and the right not to be subjected to torture or other cruel treatment. Violence is a phenomenon that has been affecting Venezuela for decades and which, in the current context of humanitarian crisis, aggravates the deterioration in the realization and enjoyment of human rights, becoming an additional factor in the forced migration of Venezuelans.

ALWAYS THE WRONG TIME, WRONG PLACE:EVER-PRESENT VIOLENCE

HOMICIDE RATES: THEN AND NOW

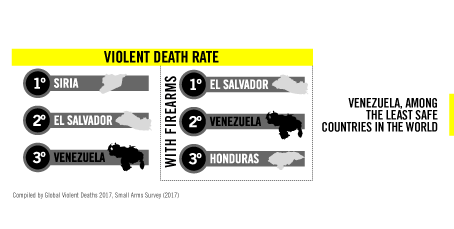

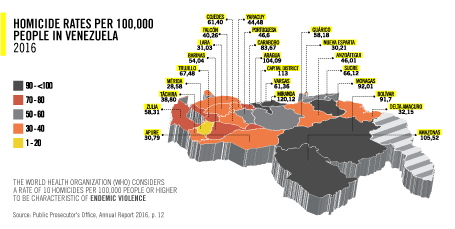

In 2016, Venezuela had the third highest rate of violent deaths in the world, after Syria and El Salvador, and the second highest rate of gun-related deaths in the world2 . According to unofficial figures, the homicide rate in Venezuela in 2017 was 89 per 100,000 people, higher than countries such as El Salvador and three times higher than Brazil3 .

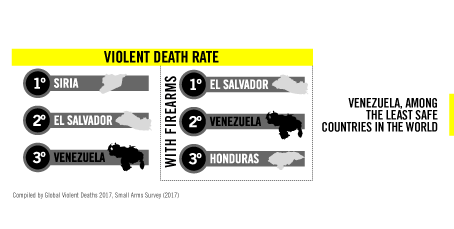

According to official figures, since 2002 the number of homicides in Venezuela has been on the increase. However, since 2010, the situation has reached crisis point; the homicide rate has not fallen below 50 per 100,000 people. According to figures published by the Public Prosecutor's Office, in 2016 the rate increased to 70.1 homicides per 100,000 people, — the highest in the country's history — which means that there were 21,752 homicides that year4 .

ARMED VIOLENCE

While in Latin America gun-related deaths accounted for 74% of homicides in 2012, in Venezuela the figure was 90% of the total5. According to the latest figures published by the Public Prosecutor's Office, in 2016, 86.6% of homicides in Venezuela were committed using firearms.6

“No entiendo de dónde salen tantas balas. A veces se caen a tiros de un cerro a otro. Es una situación que se puede dar en cualquier momento y que se puede cobrar la vida de cualquiera. A una vecina mía le mataron a sus tres hijos varones; otra vecina perdió a dos hijas por balas perdidas. Esto no es vida. Cuando a uno le matan a un hijo, matan a la familia entera”.7 MARÍA ELENA DELGADO: TRES HIJOS, UN SOBRINO Y UN NIETO MUERTOS A MANOS DE LA VIOLENCIA ARMADA

International organizations have estimated that in 2017 there were 5,900,000 small arms in Venezuela8. Regarding the measures taken by Venezuela to address armed violence, in 2011 the Presidential Commission for the Control of Weapons, Ammunition and Disarmament (Comisión Presidencial para el Control de Armas, Municiones y Desarme, CODESARME) drafted the Law on Disarmament and the Control of Weapons and Ammunition. The law sought to regulate and monitor the carrying, possession, use, registration, manufacture and sale of weapons, ammunition and weapon parts and set out penalties for unlawful acts in order to end the illicit manufacture and trafficking of weapons. It also set out to devise plans for disarmament. The law called for the sale and carrying of firearms and ammunition to be suspended for a period of two years.

However, beyond this legislation, the response of the authorities to addressing access to and regulation of firearms has been weak and has failed to control access to guns or reduce armed violence. For example, there are no ballistics records for more than 90% of the weapons that are legally in circulation and there is no evidence that an ammunition marking system has been set up. It has also been documented that 80% of the weapons confiscated and collected by police arrive at depots without magazines or ammunition, which would seem to indicate that there are no effective controls to prevent them being diverted to illegal markets9. In addition, the Disarmament Plan has not been effective and although announcements have been made that almost half a million weapons have been destroyed, local organizations who are experts in the field have questioned this claim and believe that this figure includes both ammunition and individual gun parts and that, therefore, the measure cannot be considered a success.

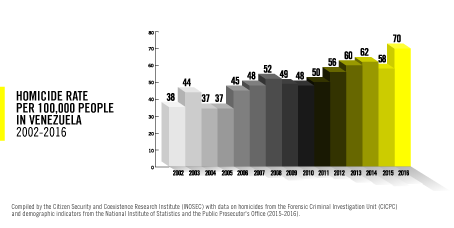

Urban Violence

Most of the states with the highest homicide rates are part of the northern coastal region of the country, which is characterized by large urban concentrations and intense economic activity. According to experts, there are a number of factors that explain the levels of violence in urban areas: the combination of a concentration of wealth and social inequality combined with exclusion; the proliferation of clandestine economic activities such as drug and arms trafficking; an ineffective response state, especially the inability to control weapons; the excessive use of force by the security forces; and the weakening of the justice system10.

Furthermore, there are indications of a recent increase in homicides in states in border areas where illegal activities linked to smuggling or mining are at the source of the violence.

The victims of Violence: young men living in poverty

Según la Encuesta Nacional de Victimización (ENV) de 2009, las víctimas eran, en su mayoría, hombres (81,13%), jóvenes (15 a 24 años: 36,61%; 25 a 44 años: 44,12%) y en situación de pobreza.11 De acuerdo con Unicef, en el año 2012, Venezuela era el tercer país del mundo con la tasa más elevada de homicidios de hombres jóvenes menores a 20 años.12 En el año 2013, el 94,4% de las víctimas de homicidios fueron hombres; el 43,4% de éstos de una edad entre 15 y 24 años, y el 45,5% entre 25 y 44.13 Datos no oficiales de organizaciones locales estiman que en el año 2017, las víctimas de la violencia fueron en su mayoría jóvenes (el 60% tenían entre 12 y 29 años de edad) y hombres (95%).14

El grueso de las víctimas de la violencia armada, ya sea que provenga de la delincuencia o del Estado, son los hombres jóvenes que viven en los barrios más pobres del país. Amnistía Internacional considera que esta caracterización de las víctimas en Venezuela es de suma gravedad: los hombres jóvenes están a riesgo de morir por la violencia armada sin que el Estado venezolano haya implementado medidas efectivas para contener y minimizar su victimización.

Impunity for common crimes

Venezuela has not been able to reverse the extremely high levels of impunity for homicide , estimated at over 90%. 15 ; On the contrary, it has systematically concealed official figures on the number of people who die annually as a result of armed violence, especially in cases where state security officers are involved. This lack of transparency is the result not only of the absence of official information, but also of the persistent refusal to allow relatives access to the case files on extrajudicial executions.

Fighting violence with more violence

Amnesty International has documented how the Venezuelan state has committed serious human rights violations, such as torture, extrajudicial executions and enforced disappearances, during public order operations for decades 16. Today, the state is still failing to change its response regarding maintaining public order and the use of force.

According to Amnesty International’s analysis, the various security plans implemented by the Venezuelan authorities between 2000 and 2017:

- That adopt comprehensive, preventive and potentially effective approach were displaced by highly repressive and excessive measures. The ministers responsible for public security remained in office for an average of a year and five months, which may be one of the reasons for the lack of continuity regarding the implementation of public security policies.

- Have been guided by a heavy-handed logic that considers crime that poses crime as an “internal enemy.”

- Have prioritized the use of repressive methods with reactive police operations to combat crime during which illegal searches, extrajudicial executions and torture were reported.

- Have been influenced by a military approach to policing, in the framework of which excessive and abusive force has been regularly used and, in some cases, lethal force with the intent to kill has been used.

- Renew problematic measures that employ the same mechanisms and procedures, which in addition to generating human rights violations are ineffective in reducing homicides. Regardless of what the plan is called, it is essentially the same excessive measures that generate abuses and do not work.

What is the outcome for a criminal? Either prison or six feet under. Because that is a criminal's final destination.17 Head of Regional Command No. 5 deployed in the framework of the Bicentenary Security Plan (DIBISE), 2010

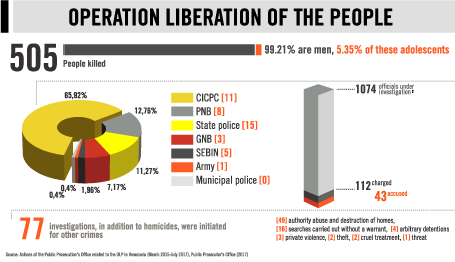

The Operation Liberation and Protection of the People (OLP) is one of the most recent examples of repressive operations implemented by the authorities, which was purportedly aimed at "freeing" communities by protecting them from the criminal violence committed by criminal gangs. Military units participated in the implementation of this plan which resulted in thousands of cases of serious human rights violations, including arbitrary arrests, extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances and infringements of the rights to privacy, physical integrity and due process. It is also worrying that senior government officials have reported "the killing of criminals" as a "success" during some of these operations.

“Of the 12 states in the country where the OLP18 has been deployed, the combat report is as follows: deployed officers, 16,799; people arrested for various crimes, 931, of which 113 are foreigners; gangs broken up together with their leadership, 27; criminals killed during clashes...52.”19. Minister for Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace, 12 August 2015

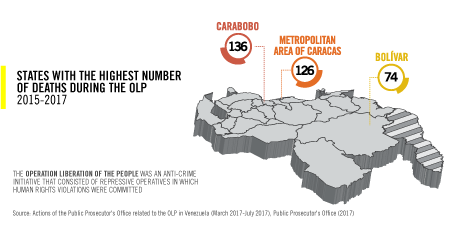

In the framework of the OLP, the majority of deaths occurred in states of the north-coastal region of the country and in Bolívar state, where the highest homicide rates are also concentrated. This suggests that the highest number of operations or the most lethal operations were carried out in the areas that report the highest rates of violence: violence was responded to with more violence.

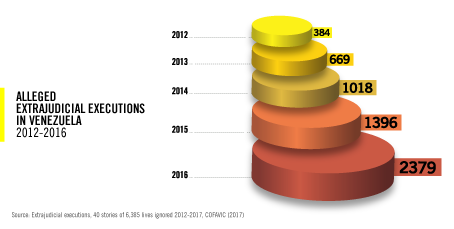

According to the Attorney General's Office ,20 between 2015 and June 2017 there were 8,292 alleged extrajudicial executions: in 2015 there were 1,777 alleged extrajudicial executions, representing 10% of the total homicides that year ;21 in 2016 it was reported that 4,667 people had died at the hands of the security forces, which corresponds to 22% of all homicides ;22 and between January and June 2017, it was revealed that 1,848 people had been killed by the security forces 23.

Furthermore, The Venezuelan NGO Committee of Relatives of Victims of the Events of February and March of 1989 (COFAVIC) has documented 6,385 cases of extrajudicial executions that occurred between 2012 and 2017 and the numbers are increasing. In 2016, 2,379 cases were recorded, 70% more than in the previous year. Once again, research confirms that the great majority of these victims were men under 25 and from poor neighbourhoods. In the first quarter of 2017 there had already been an increase of 11% in recorded extrajudicial executions compared to the same period in 2016.24

The Venezuelan State, in addition to failing in its obligation to guarantee and protect the right to life and personal integrity, when for decades it has implemented ineffective policies to reduce violence, It violates human rights when it reacts to violence with more violence.

Who are the victims of extrajudicial executions?

Amnesty International documented eight cases of extrajudicial executions between 2012 and 2017 that highlight the impacts of institutional violence in a way that statistics cannot. These cases reveal a clear pattern:

- They were young men aged between 16 and 29.

- They were fathers of small children.

- They helped support the family financially.

- They lived in poor neighbourhoods.

- Most had completed secondary education.

- They were workers: taxi drivers, waiters, cooks, mechanics.

- They were often killed in front of their relatives and children.

- Their deaths occurred in the context of security operations.

- They died of gunshot wounds to the front of their bodies –thorax, neck, and head.

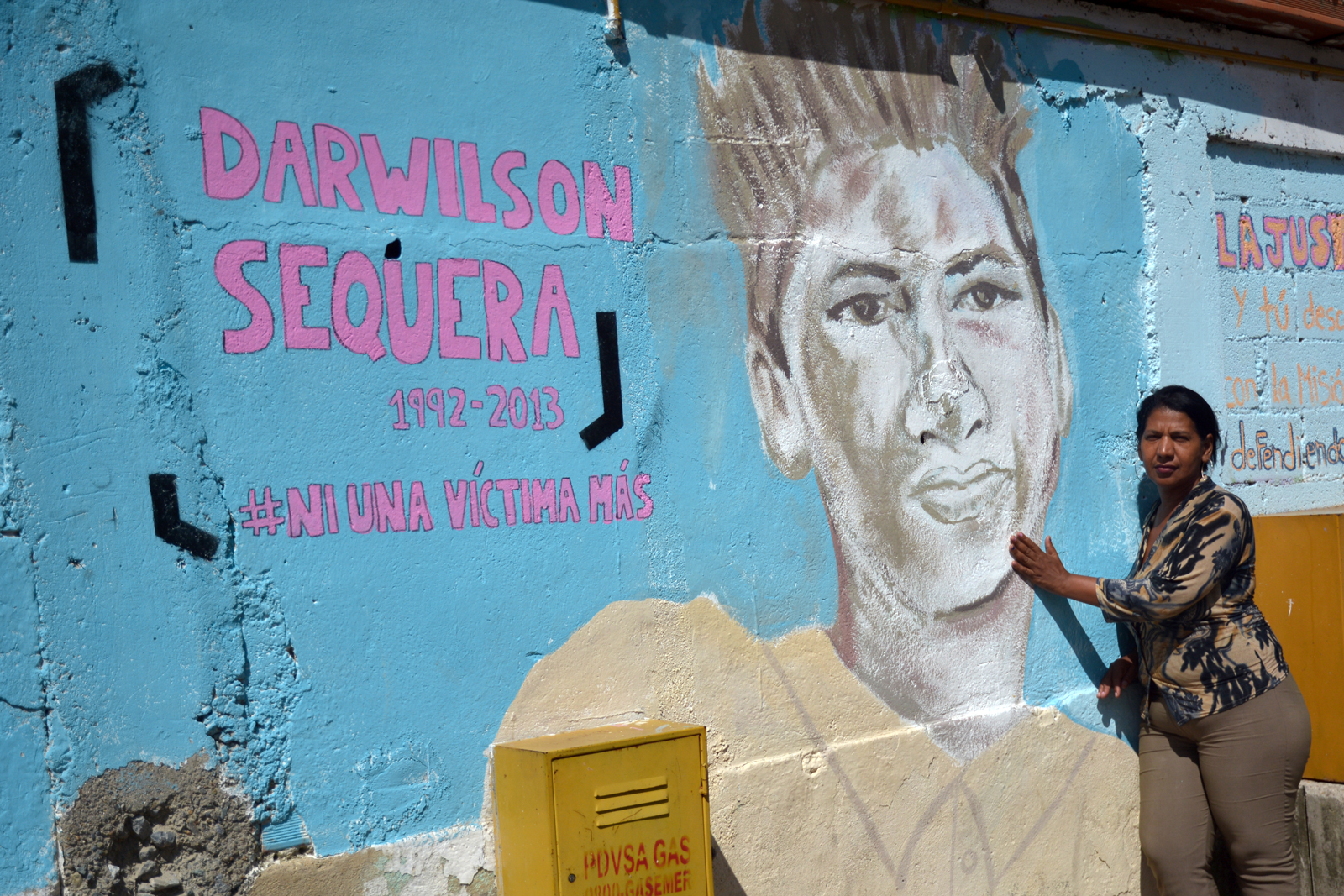

AFTER RAIDS, THREATS AND EXTORTION, DARWILSON WAS EXTRAJUDICIALLY EXECUTED IN FRONT OF HIS FAMILY

20-year-old Darwilson Sequera was extrajudicially executed on 11 June 2013 during a Forensic Criminal Investigations Police (CICPC) operation. According to the information obtained by Amnesty International, 30 police officers carried out the operation in which he was killed. According to reports: “they positioned themselves on the roof of the house by climbing up a lamppost and threatened to break down the door if those inside did not open up.” Darwilson Sequera and his younger sister went up onto the lower roof of the house, where officers caught them. His sister saw them shoot her brother. Their mother heard them take him away, screaming with pain. The next time they saw Darwilson Sequera was at the hospital; he was dead.

As of March 2018, five years after Darwilson's death, none of the officials named in the investigation had been arrested in connection with his killing; one of those named was also implicated in another case detailed in the report.

'¿QUÉ LE HIZO MI HIJO A ELLOS PARA QUE ME LO MATARAN? '

Alex Yohan Vegas Azuaje was a 16-year-old teenager and the father of a 3-month-old girl. It was executed on March 10, 2017 by officials of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) within the framework of an OLP. He was with his family at his home in El Valle, Caracas. Between five and six officials went up to the room of Alex Yohan, who was sleeping. His father, Alex Vegas, told Amnesty International that he saw one of the officers wearing a skull mask. Every time he tried to enter the house, the officers threatened to beat him and told him that they were carrying out a PLO under the presidential order: "(...) these people were going crazy that day, really. They said it was the presidential order, which was the presidential order”.

The next time his family was able to see Alex Yohan was at the Hospital Doctor Leopoldo Manrique Terrero (known as Peripheral Car Hospital) already dead, the result of a gunshot to the heart and left lung. Upon returning to the house, relatives found a pool of blood in the room and marks of gunfire. They discovered that they had been stolen. At the close of the date of this investigation, no official had been arrested for his death.

'TANTO CUIDARLOS PARA QUE LOS MATEN EN MI CASA'.

On May 18, 2016, Darwin (28), Carlos Jampier (19), Yohandri (20) and Roswil (25), were executed in their house located in the Los Llanos neighborhood in San Bernardino, Caracas. They entered around 20 troops without identification and with their faces covered, shouting and pushing the mother of Darwin and Carlos Jampier, the sister and nephew of 9 years of these, as well as the brides of the four to leave. home. After 20 minutes shots began to be heard. The women saw that the boys, already dead, were loaded onto a truck wrapped in sheets stained with blood. The young people died from gunshot wounds to the thorax. Darwin was also shot in the neck.

When the family returned to the house, they discovered that they had been robbed. As of the investigation closing date, no official had been arrested for the death of the four young people.

'THERE IS NO REASON FOR THEM TO DISPOSE THE WEAPON, THAT SHOULD BE THE LAST MEASURE AND HERE THERE IS NO DEATH PENALTY'.

Since the economic crisis and the scarcity in Venezuela have worsened, it has been increasingly difficult for the population to access basic products in commercial establishments. It is common that in the cities of the country people must make queues of several hours outside the shops to buy food at low prices. On March 25, 2016, Luis Leal Villareal, a 20-year-old cook, left early in the morning to a commercial establishment located west of Caracas, in Catia, to be able to buy products at regulated prices. Here, an official of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) shot and arrested five of the people who were with him.

According to the police, Luis and the other five young people who were making the line with him were robbing and then confronted the PNB official. However, evidence was obtained that indicated that Luis had not fired any weapon. According to the testimony of the young people, the policeman fired without giving a loud voice and then witnessed how he acted to alter the scene of the events with the complicity of other officers.

As of the date of the closing of the investigation of this report, the official remained at liberty.

Waiting for justice: the struggle against impunity and for reparation

In addition to suffering the death of family members, surviving victims must contend with a criminal justice system with high levels of impunity and riddled with irregularities and obstacles, which leads to the failure to investigate, prosecute and convict those responsible for gun violence and homicides. According to the Committee of Relatives of Victims of the Events of February and March of 1989 (COFAVIC), impunity in cases of human rights violations in Venezuela reach 98%.25

In the cases included in this report, certain patterns of denial of justice have been identified, ranging from failures in the initial stages of investigation to harassment, threats and mistreatment of victims' relatives by staff of the Attorney General's Office and from the courts:

- In many cases, officials of bodies responsible for forensic investigations, namely of the Forensic Criminal Investigations Police (CICPC), are those who carry out the killings.

- Officials under investigation always remain on active duty.

- There is a significant delay by the CICPC in handing over key documentation that would enable the investigation to progress and no effective response from prosecutors.

- Some relatives said that they have been told by prosecutors to look for witnesses and evidence themselves.

- In cases where accusations have been made, the investigation stagnates and the case seldom reaches trial. The identification of those responsible does not translate into obtaining justice.

- The practice of repeatedly changing prosecutors also creates delays in the process.

- Relatives and their lawyers do not have access to case files or some key documentation, either because prosecutors do not issue copies in a timely manner, or because the relatives do not have the resources to pay for them (relatives have to pay for copies which as of May 2018 cost almost the monthly minimum wage).

- It is common for relatives to receive threats and mistreatment, including from prosecutors, to try to make them abandon their search for justice.

- In cases of harassment and threats, the protection measures requested by the families are not granted.

None of the victims interviewed for this report had received comprehensive reparation, including financial compensation and psychological assistance. Relatives experience long-term economic effects following the killing of a family member. In the case of mothers, many are housewives, do not have formal employment, are unemployed, because of the economic crisis, work in the informal sector (home businesses, street vendors or domestic jobs), or earn the minimum wage and do not have sufficient income to support their families. In the cases documented by Amnesty International, the majority of the victims helped support the family financially. The loss of a relative becomes more significant in the current context of a serious economic crisis in which hyperinflation and shortages of food and medicines particularly affect those in the most vulnerable and socially excluded communities.

The failure to provide comprehensive reparation, including not only access to justice, but also financial compensation and psychosocial support, further entrenches impunity and also deepens the social exclusion of victims' families, perpetuating cycles of revictimization for the thousands of families whose rights have been violated in the context of public security operations.

Conclusions and recommendations

Violence and the abusive use of force are among the main human rights challenges that Venezuela has been unable to resolve. Gun violence and crime result in high homicide rates and thousands of victims each year, most of which are young men living in poverty. These homicides, although committed by individuals, are ultimately the responsibility of the state, which has a duty to act appropriately and with due diligence to prevent them through the investigation and punishment of those responsible for these deaths. Venezuela has also failed to publish statistics regarding public security and to deal effectively with the availability of guns in society at large, which has a direct impact on armed violence.

Amnesty International, in addition to identifying different flaws in government policies, is extremely concerned at the authorities' support for the intentionally lethal use of force and extrajudicial executions targeting mostly young men living in poverty. Such actions stem from an approach which sees these young men, by virtue of their social profile, as criminals and subsequently portrays them as "internal enemies" to be eradicated. In the context of public order operations and law enforcement, the authorities have an obligation to guarantee respect for the physical integrity and life of all and, when appropriate, to arrest those suspected of committing crimes and breaching the law.

It is imperative that the authorities in charge of public security radically change their approach to public security. A policy is needed that puts human rights at the centre, with clear deterrent approaches, effective oversight mechanisms and support for those living a situation of social exclusion, who are most at risk of abuses. State policy must also include an effective system of gun control that is transparent, can be monitored by civil society and that genuinely prevents corruption and weapons being diverted back into circulation.

Amnesty International, therefore, calls on the Venezuelan authorities to adopt the following recommendations:

- Refute messages that support the policy of repression, including the abusive and intentionally lethal use of force against young people living in poverty.

- Implement a policy of transparency and disclosure regarding information to enable appropriate public policy and measures to be adopted (both preventive measures to address violence, as well as police reform and reducing the number of guns in circulation) and to enable civil society organizations to exercise a social oversight role.

- Initiate immediate and urgent investigations into the cases detailed in this report and create a mechanism for prioritizing investigation and punishment of extrajudicial executions.

- Ensure that police act in accordance with the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials.

- Resume implementation of the measures to reduce the number of guns in circulation recommended by CODESARME and strengthen policy on the control and regulation of arms.

- Agree to visits by the special procedures of the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights whose mandates are relevant to the concerns set out in this report.