Martes, 27 de junio, 2023

Burundi has, over the years, been beset with civil wars, ethnic violence, poverty, and economic instability. In 2008, Burundi became so indebted that it was included on the World Bank’s list of Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC). Its inclusion on the HIPC list qualified it to be admitted to multilateral debt relief initiatives of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF-led debt cancellation and restructuring programmes have however failed to comprehensively address Burundi’s debt problem.

Like most countries, Burundi was hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in reduced capacity to both service debt and realize socio-economic rights obligations to its citizens. For instance, Burundi’s allocation to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programmes was reduced from 1.9% in the 2019-2020 financial year to 0.9% in 2020-2021. To find reprieve, Burundi participated in the G20-sponsored Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) which allowed the country to postpone paying interest on some of its debts, as well as provided debt relief of USD 0.93 million in 2021 from the Exim Bank of China and Kuwait Fund. In 2020, Burundi obtained USD 150 million from the IMF under the Catastrophe Containment Relief Trust. In 2021, it borrowed another USD 76 million from the IMF Rapid Credit Facility to support its response to, and recovery from the pandemic. These reprieves were not enough to enable a full post-Covid recovery. Consequently, by 2022, Burundi was once again deep in debt, with public debt at 66% of GDP, which although considered by the IMF as sustainable, put the country at high risk of debt distress. To date, Burundi’s domestic debt to GDP stands at 46% owed largely to Burundi’s central bank and holders of government bonds and treasury bills, although foreign-owned debt has been increasing.

Burundi has made efforts to raise domestic revenue. Seven new tax measures were implemented, including a new tax on mobile phone megabits, and a widening of the rental tax base. While this appears to have boosted revenue from 18.5 % of GDP in the 2020-2021 financial year to 18.8% of GDP in 2021-2022, Burundi remains heavily reliant on donor funding – particularly in the health sector. External resources accounted for 15.2% of funding for Burundi’s 2022-2023 budget. Although Burundi’s revenue to GDP ratio has been on a steady increase, even during the civil war when rapid military spending boosted tax revenue, most of current tax revenue (38%) is derived from indirect taxes on goods and services which disproportionately affect the poor. Curbing systemic corruption has been cited as one of the ways of improving tax revenue. For instance, Afrobarometer reported in 2014 that 46% of respondents believed that “most” or “all” Burundi tax officials are corrupt. The IMF estimates that tax exemptions amount to the equivalent of 18.3% of total Burundian revenues.

Implications of debt on the right to health in Burundi

Burundi is one of the top 5 least developed countries in the world and the poorest in sub-Saharan Africa. Its National Health Development Plan and national health policy have ambitions of providing universal health coverage (UHC) but currently, free healthcare is only provided to children below 5 years old, pregnant mothers, and retirees and their dependents. Maternal and child mortality remains high at 334 deaths per 100,000 live births, and 78 deaths per 1,000 live births.

To aggravate matters, Burundi’s high inflation rate has had a negative impact on social determinants of health and therefore the health system. The overall inflation between July 2021 and July 2022 was 19.1%, thus reducing the spending power of households. According to UNICEF, “64% of Burundian children are deprived of at least 3 of the 7 dimensions of child well-being, namely education, food, water, sanitation, protection, shelter and information”.

Burundi relies heavily on donor funding to supplement its health budget. However, donor funding focuses on immunization, HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria leaving other vital areas underfunded. Consequently, 52% of Burundian children are malnourished.

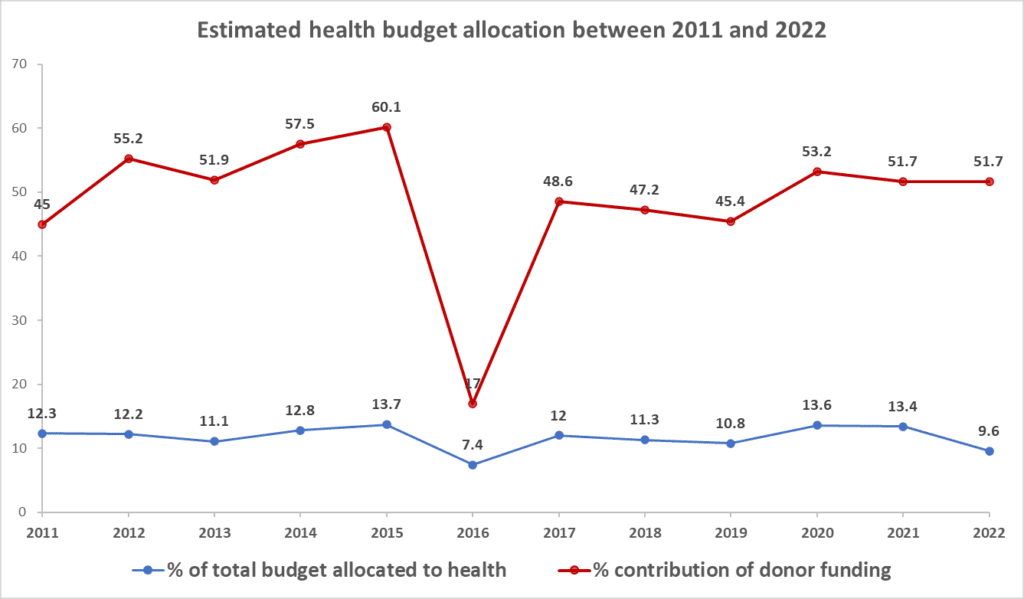

Despite signing the Abuja Declaration, which seeks to increase government spending on health to at least 15% of its national budget, Burundi’s allocations to health, including donor funds, consistently fall short of this target. In the 2022-2023 budget, Burundi allocated only 9.6% of its budget to health. To increase public investment, the country has allocated 56% of the 2022-2023 health budget to health investment which includes the building of hospitals, and buying of equipment and technology. Following the late President Nkurunziza’s contested third-term run for the presidency, subsequent political upheavals, sanctions and withdrawal of donor support, the country opted to undertake massive cuts in social spending. This resulted in a significant reduction in health spending in 2016 as indicated below.

Health sector funding, 2011 – 2023

What’s next for the right to health in Burundi?

In view of the increasing internal and external pressures such as public debt and revenue shortfalls, global challenges such as climate change, Covid-19 aftershocks, and the disruptive effects of the war in Ukraine on commodity prices, Burundi continues to face budgetary deficits that undermine investment in health. The situation has been compounded by rapid corruption and political uncertainties which threaten the country’s social stability.

The easing of sanctions in November 2021, and renewed donor engagement, however, should support Burundi’s economic recovery. For this to happen, Burundi should prioritize social spending, promote transparency and accountability, undertake tax reform – including the curbing of tax exemptions – and manage inflation. At the global level, lenders should prioritize debt relief to enable Burundi to cope with global crises, while addressing pressing socio-economic rights issues.